Verification of Neural Networks

A problem in two parts

Taken from the VNNCOMP 2021 benchmarks

The verification

Loading diagram...

The goal is to linear the output layer of the neural network and verify the constraints

Common activation functions

Loading diagram...

R(x)={0xx<0x≥0

Loading diagram...

LR(x)={axxx<0x≥0

Other notable activation functions

Loading diagram...

S(x)=1+e−x1

Loading diagram...

T(x)=e2x+1e2x−1

Linearize the activation functions

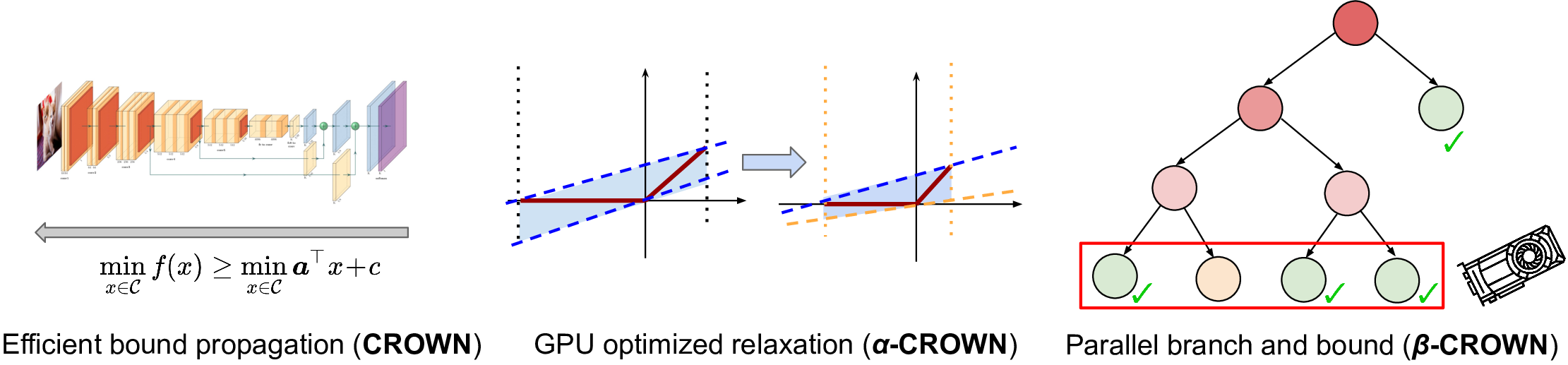

The approach used by α-β-crown, winner of VNNCOMP 2021, 2022 and 2023 is to linearize the activation functions, reducing the error introduced by the approximation with tunable parameters.

Convex relaxation of Neural Networks

To deal with intractability, convex relaxations can be used. For instance, Planet relaxation substitutes the ReLU function y=max(0,x) with

y≥0y≥xy≤u−lux−u−lulwhere l and u are the lower and upper bounds of the input x. They can be obtained directly or estimated.

Propagate bounds

Bound propagation is a key step in guiding the search for a solution. State-of-the-art tools include LiPRA and PRIMA.

dlinear's current naive implementation only propagate explicit bounds and equality constraints.

These functionalities can be extended by considering the interval bounds of the input variables and propagating them through the graph of constraints.

Sum of infeasibilities

Comparison

| Tool | Strict constraints | Output eq y | Correlated inputs | Unbounded x | Or | Precision | Efficient |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| dlinear | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | × |

| alpha-beta-crown | ✓* | × | × | × | × | 10−10 | ✓ |

| neurosat | × | ✓ | × | × | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| nnenum | × | ✓ | × | × | × | 10−10 | ✓ |

| Marabou | × | ✓ | ✓ | × | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

SMT components: Terms and formulae

- f∈VB: propositional variables (Formula)

- x∈VR: real-valued variables (Term)

- a,c∈R: constants (Term)

- ∼∈=,=,<,≤,>,≥: comparison operators

Conjunctive normal form

Most SMT solvers expect the input in CNF form, where lij are literals

(l00∨⋯∨l0m0)∧(l10∨⋯∨l1m1)∧⋯∧(ln0∨⋯∨lnmn)If-then-else terms

If f,f1,f2 are formulas, ite(f,f1,f2) is a formula equivalent to (f1∧f2)∨(¬f1∧f3)

If t1,t2 are terms and f is a formula, term-ite(f,t1,t2) is a term

Piecewise linear functions to ITE

Piecewise linear functions can be represented using if-then-else terms

; ReLU

(declare-const x Real)

(declare-const y Real)

(assert (= y (ite (<= x 0) 0 x)))ITE to CNF

The if-then-else term can be converted to CNF by introducing a fresh variable c with the following equisatisfability relation

f(term-ite(g,t1,t2))≡f(c)∧ite(g,t1=c,t2=c)

e.g.

term-ite(g,1,2)=term-ite(h,3,4)becomesite(g,c=1,c=2)∧ite(h,c=3,c=4)Max encoding

The max function can be seen as a special case of an ITE term. Exploiting its characteristics, introducing two fresh variables a1,a2 allows to encode it directly in CNF:

y=max(x1,x2)⟹(y−x1=a1)∧(a1≥0)∧(y−x2=a2)∧(a2≥0)∧(a1≤0∨a2≤0)Linear layers, non-linear activation layers

Given a neural network with L layers, we can divide them into two categories:

- Linear layers: fi(x)=Wix+bi

- Input: x∈Rm, weights: Wi∈Rn×m, bias: bi∈Rn

- Activation layers: non-linear f

- Piece-wise linear functions

- General non-linear functions

Tightening the bounds

Converting all the layers of a neural network up to an activation layer to a linear constraint allows to compute the bounds of the output of the activation layer, as long the input is bounded.

−1≤x1≤1−4≤x2≤7r1=2x1+3x2−1r2=4x1−2x2+3⟹⟹−15≤r1≤22−15≤r2≤15Fixing the piecewise linear functions

If the bounds on output of the activation layer are strict enough, it may be possible to fix the piecewise linear term.

0≤x1≤14≤x2≤7r1={2x1+3x2−10if 2x1+3x2−1>0otherwise⟹r1=2x1+3x2−1Sum of Infeasibilities

Instead of adding the non-fixed activation layers to the constraints of the LP problem, they can be used to minimize the sum of infeasibilities.

Sorting by the violation they introduce gives us a way to prioritize the search for the solution.

mins.t.r1−(2x1+3x2−1)+r2−1≤x1≤1−4≤x2≤7r1,r2≥0r1≥2x1+3x2−1r2≥4x1−2x2+3Completeness vs Real world

SMT solvers aim for a complete approach, a mathematical solution of the problem, employing symbolic representation of the inputs and exact arithmetic (when possible).

In the real world, however, speed of the computation is usually the main concert, hence floating point arithmetic is almost always used.

As a result, it can happen that the solution found by the SMT solver is not the same as the one computed by the neural network (e.g. OnnxRuntime).

Future work

- Benchmarks

- Other heuristics to optimize the search for the solution

- use overapproximation of bounds to reduce the search space

- How much completeness are we sacrificing?

References

- Symbolic representation with focus on ITE and max terms

- Efficient Term-ITE Conversion for Satisfiability Modulo Theories

- Different approaches to optimize the solution search in the exponential subproblem tree

- Floating-Point Verification using Theorem Proving